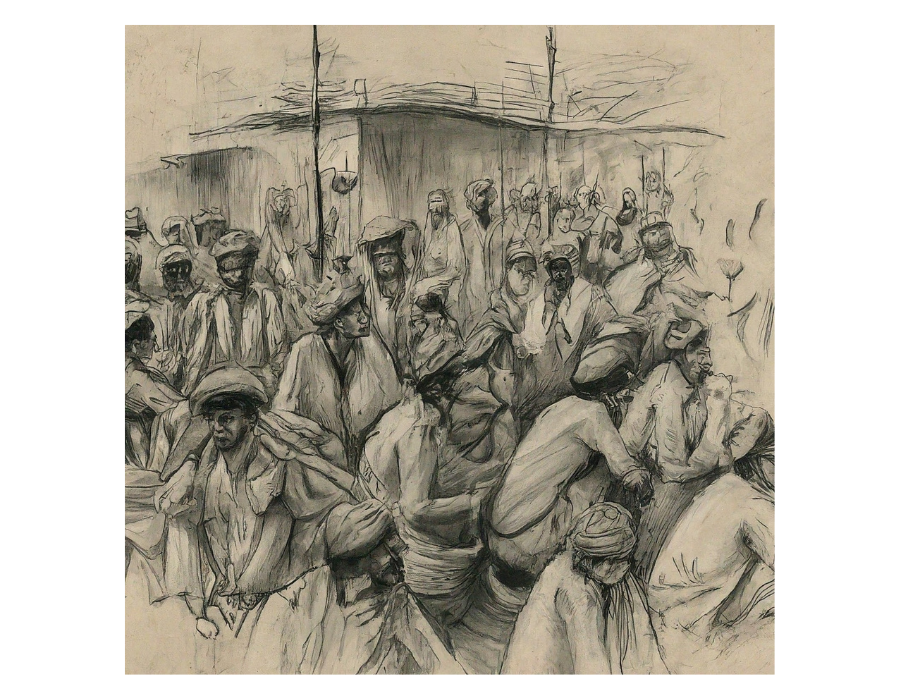

Bringing visibility to the lives of daily wage workers

- Social Compact

- Feb 7, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Feb 9, 2025

Narrated by Jagalinga Dhangar, Social Compact

Co-authored by Jagalinga Dhangar and Rebecca Shibu, Social Compact

Ravi, roughly 47 years old, came to Mumbai from Uttar Pradesh in search of work about 10 years back. In Mumbai, he lives in a rented home with his spouse and 4 daughters. He is the only breadwinner of the family. As a daily wage worker, he has been working as a carpenter ever since he migrated to Mumbai. Given the nature of his work, which is inconsistent and at times limited, Ravi, is at the Sakinaka (Mumbai) labour naka at the early hours of the day amidst its crowded street waiting to be noticed by a contractor who could give him a job.

I met Ravi at the Sakinaka Worker Facilitation Centre (WFC) run by Aajeevika Bureau. In our conversation, indicating the scarcity of work, he tells me, “Work was going well for some time but now I do not get any regular work, it’s always for 10-15 days of the month. It is not enough for me.” While wondering about how the days with work look like, he shared about the generally low daily wages and often facing issues of being paid wages below the amount committed by the contractor. In his accounts of frustration with the contractors being fishy about payment, many daily wage workers’ experiences in India would find immediate resonance.

Ravi has now filed a case with the India Labour Line to seek help to get his entitled dues back from the contractor. However, this isn’t the fate of many daily wage workers in India who find themselves facing issues like this. Many – (a) fall into the trap of bonded labour with the contractor in hopes of eventual payment, (b) end up taking high interest loans from informal moneylenders or (c) never find the agency to seek remedial recourse to ultimately forfeit their dues.

Others like Ravi and excerpts of my memory from Yadgir

Ravi’s plight is not isolated. As Nivedita Jayaram from Aajeevika Bureau (2018) reports, seasonal migrants in the construction sector alone face an estimated wage loss of Rs. 6,400 crores, annually, due to non-payment of wages. This is only the reality of seasonal migrant workers from 2018, the expansiveness of this challenge in 2024 around the entire country, across so many forms of informal factions of work has only grown by multitudes.

Workers like Ravi who are reliant on their daily wages only think of covering, as basic as, their household meals for the next 2-3 days with the income of one day, which may be anywhere between Rs. 400-450 or less if the hours of work vary. They live in continual worry of how they would carry on their lives. Being present at the labour naka doesn’t guarantee any work and payment of wages of the day, the unregulated nature of work has over the years enabled contractors and sub-contractors to stay dubious. Additionally, in Vikas Kumar (2022) reports for Citizen Matters that in India Labour Line’s experience in Bengaluru, 40-50% of complaints of non-payment of wages are filed by workers belonging to backward castes, also hailing from very backward districts of Karnataka like Kalaburagi, Koppal, Raichur and Yadgir.

Yadgir is my home where I’ve spent 15 years of my life and over the years, I have observed people moving for various reasons. It has ranged from not being able to historically own or inherit agricultural lands, lacking resources for irrigation of their lands that lead to lesser yields in a year or their inability to make ends meet in their homes with their work in Yadgir. Cities like Bengaluru and Mumbai attract a lot of workers from Yadgir and other neighbouring districts. They have a higher daily wage that encourages people to finally make the move in hopes of a better life. Pinak Sarkar for the Journal of Migration Affairs (2020) notes that workers from poor or backward districts / states prefer to migrate to industrialized and urbanized states and this stands true in my own experience of observing Yadgir’s migration flow. Hence, when these migrant workers reach destinations, they exist with little to no agency and find themselves falling into the trap of contractors who barely stick to their commitments.

As they navigate their ways around a new city, many challenges confront them as Aarya Venugopal and Ameena Kidwai report for The Wire (2022) the inconsistencies in operation of ration cards from their home state, access to any legal recourse and generally lacking a support system around them who can offer solace in times of dire need. Bogged down by these challenges of food, safety and security - the courage to face up to a legal battle for non-payment of wages finds space in the fate of only a few. In the absence of a formal relationship with job contracts and a well-functioning grievance redressal system, workers are left with only verbal agreements, barely remembered and conveniently forgotten.

In the conversation with Ravi, he expressed feeling burdened with the responsibility of educating and marrying off his daughters. Breaking down the number of expenses that stare at his future and his ability to financially safeguard his family, he states and wonders, “It takes at least Rs 10 lakh for the marriage of one girl in my village, where will I get that kind of money from for all my 4 girls?” In my interactions with over 15 male workers and 1 female worker so far, 80% of workers are migrants. And like Ravi, in Sakinaka and Ghansoli WFCs run by Aajeevika Bureau, all have shared their life stories that have followed a similar trajectory. Most reach at the early hours of the day to look for jobs at the nearest labour naka or have been engaged on contract in a steel, garment or electric factory nearby. While their daily work looks distinct, what ties their lives together is their inability to lead lives of financial security and no access to social security and safety nets.

Social Compact’s learnings from workers’ lived experiences

Social Compact’s baseline across 60+ companies engaging industry-engaged informal workers maps all these companies across 180+ indicators which include payment of wages, issuance of appointment letter and pay slip, occupational safety metrics, among others. The baseline shows that about 58% of the workers in these companies did not receive an appointment letter. The letter, being the most basic form of contract, states the terms of engagement of a contract worker, the entitled payment for the said work and the confirmation of the job, till date, is not mandatory, and only viewed as best practice. Now, for daily wage workers who are outside of the purview of organized industries, the precarity of their jobs is higher especially in the absence of any formal systems that surround them.

Solving for the insecurity felt by over 200 million people

My conversation with Ravi and the other workers have left me with many questions and reflections about the ecosystem of care extended to the informal workers. It makes me wonder about the preparedness of the country to see the rise of its informal economy.

To this date, Social Compact with Aajeevika Bureau and Centre for Social Justice runs 7 industry-backed worker facilitation centers in Maharashtra and Gujarat that hears from the workers to (a) inform its own work, (b) builds awareness on the ground and (c) link workers with government entitlements. In the last 3 years, it has achieved success in facilitating over 24,500 people and communities that otherwise stay on the margins, unreached. A distinct capability of these facilitation centers is to offer remedial recourse to workers free of cost. Through this the centers have been able to retrieve over Rs. 60,00,000 worth wages back from the contractors after mediation.

Lalita T reports for the Citizen Matters (2022) that basis Building and Other Construction Workers’ (BOCW) officials, Mumbai Metropolitan alone has 40 such worker facilitation centers run by distinct organizations with a reach of roughly 35-40 lakh workers. However, their efforts remain disaggregated and are yet to sum up to respond to the scale that informality in India has grown into. Would moving out of our siloes and addressing this together ease the vulnerability felt by so many at work? I wonder.

When thinking of solutions, one is always struck by the intensity and layers of the challenge at hand. If it has existed for so long, it clearly does not have a quick solution. It needs investment, rigor and an interest in over 200 million lives that hang by a thread of hope that there is a secure light at the end of the tunnel.

Disclaimer and Credits: Aspects of Ravi’s life like his name have been changed to maintain anonymity and respect his intent to be one of the many voices that would like to be heard. The reflections from conversations are Jagalinga’s first-hand conversations and Rebecca has translated them and brought the piece together through secondary research. All images used in the blog have been generated and edited via Open AI and Imagen.

Comments